Chapter Introduction

Acknowledging the gap between the European Union’s climate policy commitments and the Paris targets, in November 2018 the European Commission set the long-term objective of a ‘climate-neutral Europe’, to be achieved by 2050. While Europe had already met its rather unambitious 2020 GHG reduction target before the Covid-19 crisis, on the basis of past performance the equally unsatisfactory 2030 and 2050 targets currently in place would appear to be out of reach. Meeting the enhanced ambition of climate neutrality by 2050 thus poses a huge challenge and will require a radical step-up of in terms of the Continent’s climate policy efforts.

The European Green Deal, announced by the new Commission in December 2019 (European Commission 2019c) as its flagship initiative, seeks to transform this objective into concrete policies. A key pillar in this strategy is a large-scale, Sustainable Europe Investment Plan to mobilise at least €1 trillion in sustainable investments over the next decade to help meet the additional funding needs to fulfil the new policy ambitions. The Commission had estimated earlier that achieving the current 2030 climate and energy targets would require €260 billion of additional annual investment, or about 1.5% of 2018 GDP, on energy systems and infrastructure. These numbers alone offer a sobering assessment of the challenges Europe is confronted with.

Just a few months after these important announcements, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic manifested themselves, bringing profound and unexpected changes to our daily lives, our work and to the economy as a whole. Addressing the dramatic consequences of the pandemic became the number one priority for policymakers all over Europe, and for the social partners, at both a national and supranational level. For obvious reasons, the very first initiatives sought to contain the spread of the virus, with various lockdowns being imposed across Europe also in order to facilitate the upgrading efforts involving national healthcare systems which in most countries were visibly challenged by the Covid-19 ‘tsunami’. In addition to that, it soon became clear that further and more long-term measures would be needed to mitigate the damage caused by the shutdown of the economy and to protect workers against the worst consequences of the pandemic, that could be felt for several years to come.

It is time to reflect about the world after Covid-19 from an eco-sustainability perspective. The chapter argues that the environmental dividend of the lockdown was short-lived and a return to ‘business as usual’ would be a serious mistake. The climate emergency that was at the top of the policy agenda until February 2020 has not gone away and it could, in many ways, be further exacerbated by the policy responses addressing the Covid-19 emergency. It should also be clear to anyone that a ‘climate lockdown’ as a possible, desperate, last resort measure seeking to deal, in a not so distant future, with a detailed response to the climate emergency is neither possible nor desirable. This chapter elaborates further on this point by advancing a series of policy recommendations for a sustainable recovery.

The lockdown’s impact on the environment

In the midst of this crisis, one could have been forgiven for thinking that the climate emergency could be set aside for a while longer. In fact, the early phases of the economic shutdown coincided with a short window of climate-optimism, where the air of our cities was breathable, the skies were once again blue, and pictures of Venice’s unusually transparent waters were almost presenting us with the possibility that a different, more eco-sustainable, future was within grasp.

The lockdown of cities, regions or entire countries has led to a sudden drop in greenhouse gas emissions and a consequent unprecedented sudden improvement in air quality, as also documented by NASA (2020) and images by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) ( Watts and Kommenda 2020). This has been certainly a welcome if unintended consequence, but it is clear that these effects lack any structural character. There are both opportunities and risks that arise from these radical carbon footprint-shrinking measures, and policy responses need to balance short-term actions with longer-term objectives.

On the positive side, even short-term air quality improvements in lockdown regions and a subsequent drop in global CO2 emissions are undoubtedly an encouraging phenomenon. For example, the German think tank Agora Energiewende (2020) estimates, that due to This means that in 2020 Germany could reach an average reduction of emissions by 42% instead of the earlier expected 37% when compared to 1990 and thus meet its climate policy target. But could this lead to an unwarranted degree of optimism, or even to societal complacency?

The benefits won’t last forever

This optimism was however short-lived and, with hindsight, clearly misplaced. As economies began to reopen in the late summer months, our roads became progressively busier, factories and businesses started planning ahead with the view of resuming their old production and distribution processes, and a people's changing attitudes towards public transport – now viewed with suspicion as a possible locus of viral contagion - suggest that our days ahead may not necessarily be any greener.

Rebound effects can reverse any of the positive environmental effects or make things even worse for the longer-term, just as we saw at the time of the 2009 crisis. While with a 0.1% drop of global GDP during the 2009 financial crisis, global CO2 emissions fell by 1.2%, this was followed by a 5% rebound the following year (Peters et al 2012).

At the same time, empirical evidence indicates that despite the impact of the effects of the coronavirus crisis a new global peak in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels was actually reached in May 2020. Measurements by the Mauna Loa observatory in the US showed that the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere reached 417.2 parts per million in May 2020, 2.4ppm higher than the peak of 414.8ppm in 2019. . The effects of the lockdown could only slow down the increase of global CO2 concentration, but not stop it or even mask it (Harvey 2020).

And it is now clear that 2020 is also going to be the first or second hottest year on record, as global data of the first seven months of the year indicate (Scientific American 2020).

Policy responses to the pandemic do not offer a template for the climate crisis

The economic shock to people’s livelihoods, with businesses and entire sectors of the economy shutting down, Covid-19 induced redundancies and restructuring (see Chapters 2 and 6), educational systems shutdowns, travel restrictions and disruptions to supply chains causing shortages of essential goods and services demonstrates how damaging rapid responses can be. This is certainly not the way to deal with the climate crisis.

The Covid-19 crisis should enter our history books as the starkest reminder that it is best to avoid a situation in the future where, due to the lack of incremental action taken over a longer period, radical almost overnight measures might become necessary to avoid a climate catastrophe.

The sudden stop of economic activities also has the negative side effect that it reinforces the ‘growth vs. environment’ and ‘jobs vs. environment’ dichotomies that sensible climate policymakers have been eager to leave behind in recent years. Any ‘emergency break’ response almost inevitably triggers a reaction, in both decision-makers and for large parts of the public, where the priority becomes growth and jobs at any price.

GHG reductions on a territorial basis

The reduction in total GHG emissions since 1990 means that the EU – even without the one-off effect of the COVID-19 crisis - will meet its 2020 target. Projections reported by Member States show, however, that even the EU targets currently envisaged for 2030 and 2050 (that fall short of the Paris objectives) are out of reach on a business as usual basis. Meeting even these non-satisfactory current targets would need significantly more effort, not to speak about the stricter targets expected to be adopted within the European Climate Law proposal in Autumn 2020. This section looks back to the past decades and examines Member State performance in the reduction of GHG emissions in both quantitative and qualitative ways.

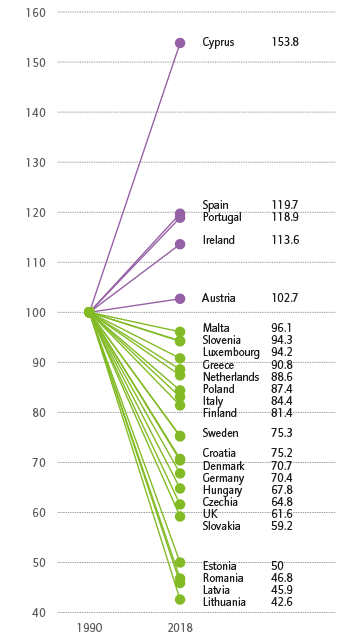

As figure 3.1 shows, most of them reduced emissions between 1990 and 2018 and contributed to the aggregate EU performance.

Figure 3.1 Greenhouse gas emissions in 2018, index (1990=100)

Source: EEA [env_air_gge].

Most emissions cuts were due to economic restructuring and not to dedicated climate policies

In absolute terms, about. New mostly due to the radical change of their economic structure during the transformation crisis of the 1990-s with Romania, Latvia and Lithuania having recorded reductions exceeding the 50 per cent mark. Germany also `benefited` greatly from the collapse of East German energy-intensive industries during the 1990-s. The overall net GHG emission reductions achieved by most Member States were however partly offset by higher GHG emissions in a few Member States such as Austria, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Cyprus that recorded increases between 2.8 and 53 percent between 1990 and 2018.